Military records can reveal a lot about someone’s time in the armed forces. Birth, baptism, marriage and census records will tell a lot of practical and formal details about their life. However, the information they provide is often clinical, adding little actual flesh to the story of the person’s life. A service document may show that someone had a good character, or that they spent time confined to barracks of an offence, but it will not expand on that man or woman’s personality or passions.

Much as the media in the 21st century seems to be focused on sensationalism, but the newspapers of the early 1900s were not backward in coming forward to try and build their readership.

The British Newspaper Archive website is a subscription-funded digital repository of more than 85m pages from periodicals dating back nearly 300 years from across the country. The site is set up with an easy-to-use search facility, allowing the user to focus a date search to within a week, and pin a location for the publication down to a country, county or town.

The website is useful when you are trying to find an article on an uncommon name or location (a search for “Smith” in 1915 bring up more than 315,000 hits for England alone). When you identify an accurate result, the information available can ass real understanding to that person’s life. I’ve found the site of particular use with funeral details, which can provide the key to unlocking a family connection that the likes of Ancestry haven’t been able to clear.

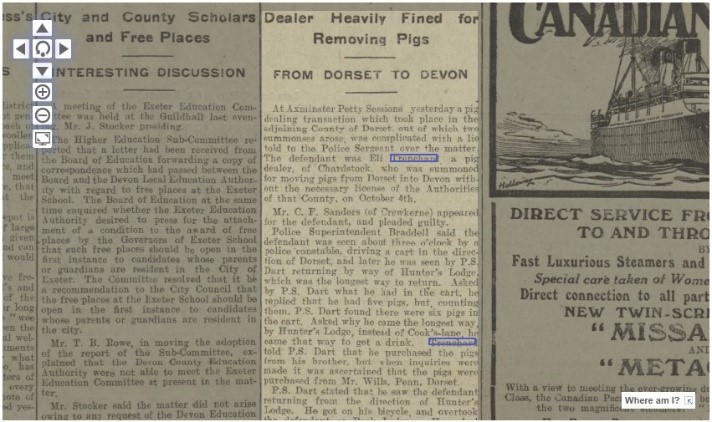

Beyond this, newspaper reports can add background to family life – a bankruptcy leading to a geographical relocation; inquest details relating to an unusual death; a court case about pigs being smuggled across a county border – that add to the character of the people involved. These news reports really tell of the lives being researched.

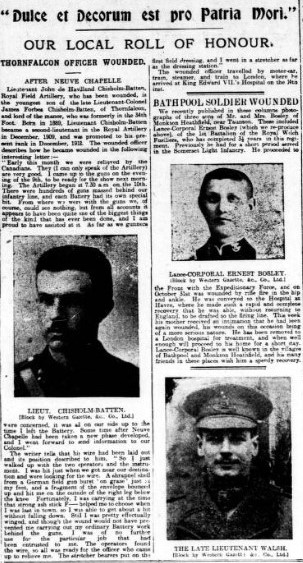

Edwardian newspapers were not above sensationalist articles, however: It is not unusual to uncover the explicit details of a suicide note that many editors would hesitate to publish nowadays. Reporters of the time were not beyond the use of euphemism to describe a shell-shocked soldier’s lack of strength or character: ‘sensitivity’ or ‘delicate nature’ being regular alternatives.

As the war rolled ever onwards, many newspapers kept a roll of honour. It is from these memorials that portraits of the fallen have been available, adding a face to the name, making their life – and their loss – somehow more real.

The shock of death, particularly when the person was very young, or their passing unexpected or unusual, was a draw for the reading public, and while mindful of sales, newspaper editors were keen to reflect public opinion. Commemoration of those who had passed was no more unusual then as it is now, and, in a non-digital world, the role of the newspaper was significantly more important to this.

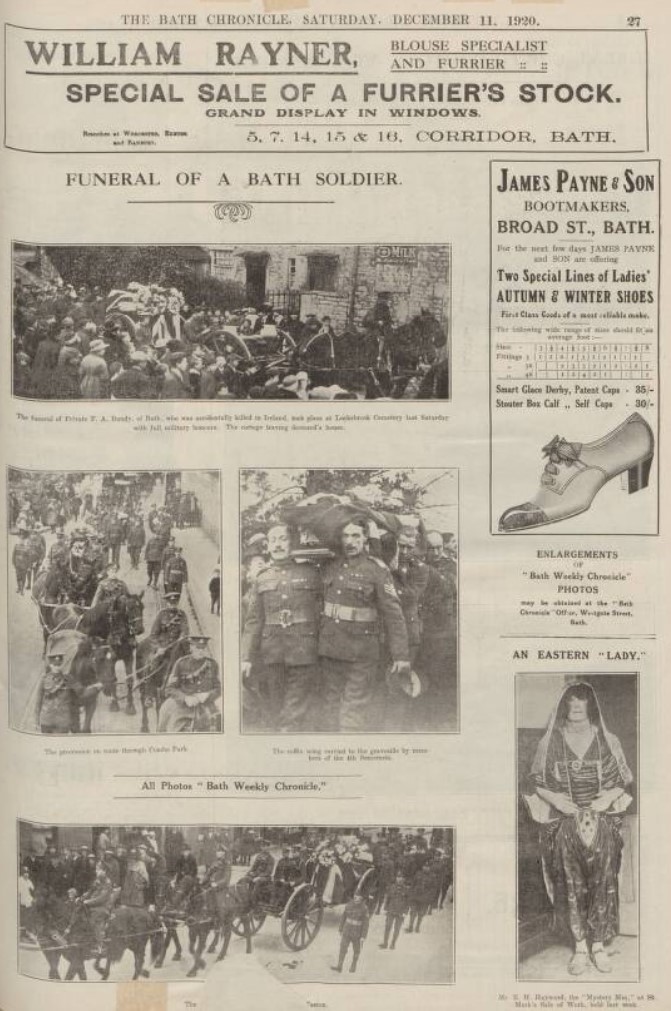

An example of this commemoration came on 11th December 1920, when the Bath Chronicle gave over a page photo spread to the funeral of Private Frederick Bundy. A member of the Somerset Light Infantry, he had died in an accidental shooting in barracks in Belfast. He was not yet seventeen years of age when he died, and the photographs of his funeral cortege made for essential reading.

The British Newspaper Archive has added an often vital link in the chain of the research I carry out, fitting in comfortably with the other online tools I use. There are, of course, other resources I access, although these are not necessarily on the World Wide Web…