On Monday the body of a man was found.. neat Newton Bridge, commonly known as the “Skew” Bridge, having been killed by a passing train… The deceased was Frank Gilbert…

The inquest was held at the Globe Inn, Newton… by the Coroner for North Somerset (Dr S Craddock), who sat without a jury.

The first witness… said the previous morning he was walking along the railway when he saw the body of a man lying on the down side. The head was separated from the body…

PC Cornish said he found four cards in the pockets of the deceased’s coat. Two were National Insurance cards, and there was an unemployment book, the last payment being dated 15-8-21.

Written on the blotting paper of the book was the following:

“It is quite dark. You still take you neck oil, and my children outside waiting. Marry the man who gave you the watch. Don’t forget to have an extra one (Guinness) over my parting. It would be murder if I ever lived with you again.”

The man’s name, “Frank Gilbert, 44 Jubilee Road, Aberdare,” was on some of the cards. Deceased was wearing a discharged soldier’s badge.

Sarah Kate Gilbert, wife of the deceased, who lives at Bristol, said she had not known her husband’s address at Aberdare. They had been living apart since he went into the Army in 1915. She had, however, met him since that date.

Witness added that she saw him on Sunday night, and went on to say that she took out a summons for a maintenance order against him last February at Gloucester. He was then working as a carpenter in Cheltenham.

The Coroner: ‘Have you ever heard him threaten to commit suicide?’

‘Yes, sir.’ She added that he did so on Sunday night when she was with him at the bottom of Park Lane, Bath. “He was always threatening me when we lived together,” she stated, and also said she had a separation order in Bath in 1913. She had a letter from him on Saturday morning in which he said that when she got the letter he would be gone. In the letter was enclosed the ticket for his suit-case, and the key.

[The letter read] “I would never dream of making a home for you as you are worth only the Gloucester man. You have ruined my life, and you will be able to sleep with… for always now. I shall be gone.”

Witness said there was no reason for him to have made any such statements, as she had had nothing to do with any man except him. He was always using threats. When she left him on Sunday night she told him to try and get on and pull himself together.

The Coroner recorded a verdict that deceased committed suicide by placing himself in front of a passing train on the Midland Railway.

Somerset Guardian and Radstock Observer: Friday 2nd September 1921

Little additional concrete information is available for Frank Gilbert’s life. No marriage certificate remains for his wedding to Sarah, nor is there any evidence for the couple in the 1911 census.

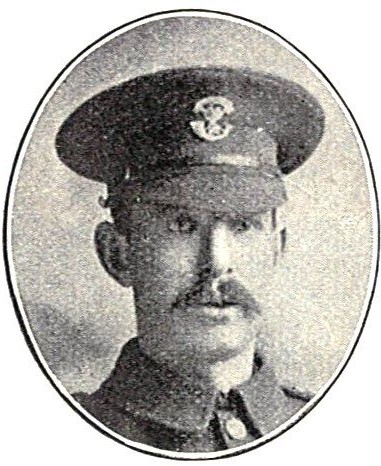

Frank’s service records no longer exist in their entirety, although his pension record give hints as to his service. He enlisted in the Royal Engineers as a Sapper on 20th November 1915, although he never saw any action overseas. He was medically discharged because of rheumatism on 11th November 1917. The document confirm he was born in 1883, and lived in Cheltenham after his discharge.

An additional newspaper report of the inquest confirmed that Sarah had two children, and that they lived with her parents in Bath. When asked by the Coroner if she intended to bury her husband’s remains, she replied that “she had no money to do it with.” [Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette: Saturday 3rd September 1921]

And so Frank Gilbert was laid to rest in the quiet graveyard of Holy Trinity Church in Newton St Loe, near Bath in Somerset. He was around 38 years of age when he took his life.