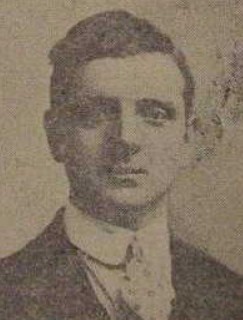

William Rea Cathcart was born in Ballymena, County Antrim, Northern Ireland, on 30th January 1887. The middle of five children, his parents were Thomas and Margaret Cathcart.

Little information is available about William’s early life, but he appears to have been a smart young man and, by his mid-20s was employed as a bookkeeper. Part of him sought a better life for himself and he took the decision to emigrate, arriving in Fremantle, Australia on board the SS Otranto on 14th November 1911.

William settled in Perth, but when war broke out, he was keen to step up and serve his King and Empire. He enlisted on 7th May 1915 but, for some reason, he wasn’t accepted for service at that time.

William did not give up, however, and he succeeded in enlisting on 30th May 1917. His service papers confirm that he was 5ft 8.75ins (1.74m) tall and weighed 150lbs (68kg). A Roman Catholic, he was noted as having brown eyes, brown hair and a fresh complexion.

Assigned to the 16th Battalion of the Australian Infantry, Private Cathcart’s unit set sail from Sydney on the troop ship A7 Medic, on the 1st August 1917. The voyage would take two months, and his unit arrived in Liverpool, Lancashire, at the start of October. It the then marched south to the ANZAC bases near Codford, Wiltshire.

It seems that the journey had exhausted William, and his health began to deteriorate. He was admitted to the camp hospital with diabetes, but moved to the No. 3 New Zealand General Hospital on 22nd November. He was emaciated and barely able to walk, constantly drinking, but eating very little.

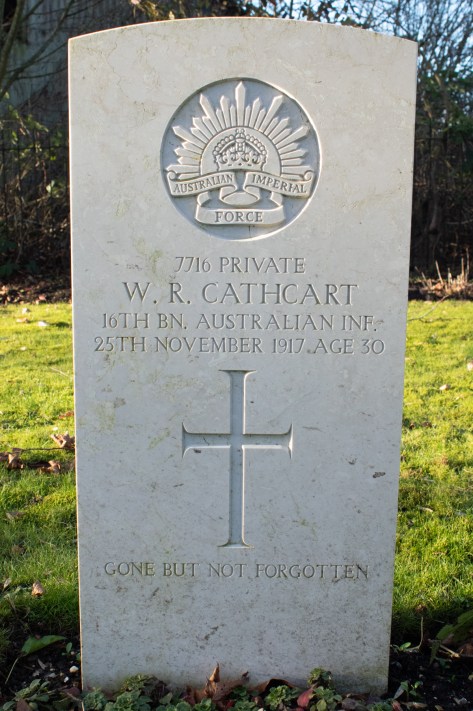

Over the next few days, William’s condition worsened. He began getting pains in his arms and legs, was sluggish and restless. The treatment he was provided would ultimately prove too little, too late. Private Cathcart passed away at 1:05am on 25th November 1917: he was 30 years of age.

The body of William Rea Cathcart was laid to rest in the ANZAC extension to the graveyard of St Mary’s Church, Codford, not far from the hospital in which he had been treated.

(from ancestry.co.uk)