Henry Gibbs was born in Wiveliscombe, Somerset at the start of 1871. The youngest of five children, he was the second son to John and Emma Gibbs. John was a farm labourer, but when he finished his schooling, Henry went in a different direction.

By the time of the 1891 census, Henry was boarding with his sister Lucy and her husband and young son. The extended family were living in Taunton, Somerset, where Henry was employed as a boot and shoemaker. This appears not to have satisfied him, however, and he soon found other work, enlisting in the Royal Field Artillery. While his army records are lost to time, he seems to have spent twelve years in service.

By the early 1900s Henry living back in Somerset, settling in Bishops Lydeard, to the west of Taunton. On 2nd May 1906, he married a young woman called Florence Gange. Fifteen years his junior – she was 20 years old to her husband’s 35, even though the marriage certificate gave his age as 30 – she a labourer’s daughter from the village, who was working at the Lethbridge Arms public house at the time of their marriage. The couple set up home in a small cottage, and went on to have four children: Ernest, Florence, Mabel and Arthur.

Henry’s work seems to have been transient. On his marriage certificate, he was noted as being a groom, but the next census return, taken in 1911, gave his employment as a labourer for a corn miller.

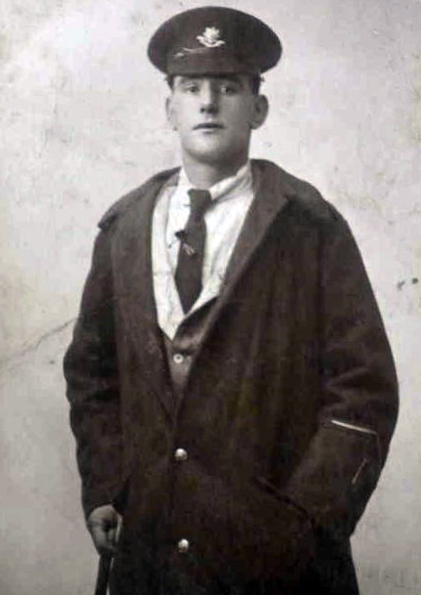

When war came to European shores, despite his growing family, Henry felt the pull to serve once more. He enlisted in the Royal Army Service Corps in the summer of 1915, with the rank of Driver. As with his previous time in the army, details are scarce, but Henry seems to have been based in Aldershot, Hampshire, or at least this is where he was based towards the end of the conflict.

Driver Gibbs had become unwell by this point, and he was suffering from oesophageal cancer. He was admitted to the military hospital in Farnham Hill, but was to succumb to the condition. He passed away on 1st September 1918, at the age of 47 years of age.

Henry Gibbs was brought back to Somerset for burial. He was laid to rest in the quiet graveyard of St Mary’s Church in his adopted home village, Bishops Lydeard.