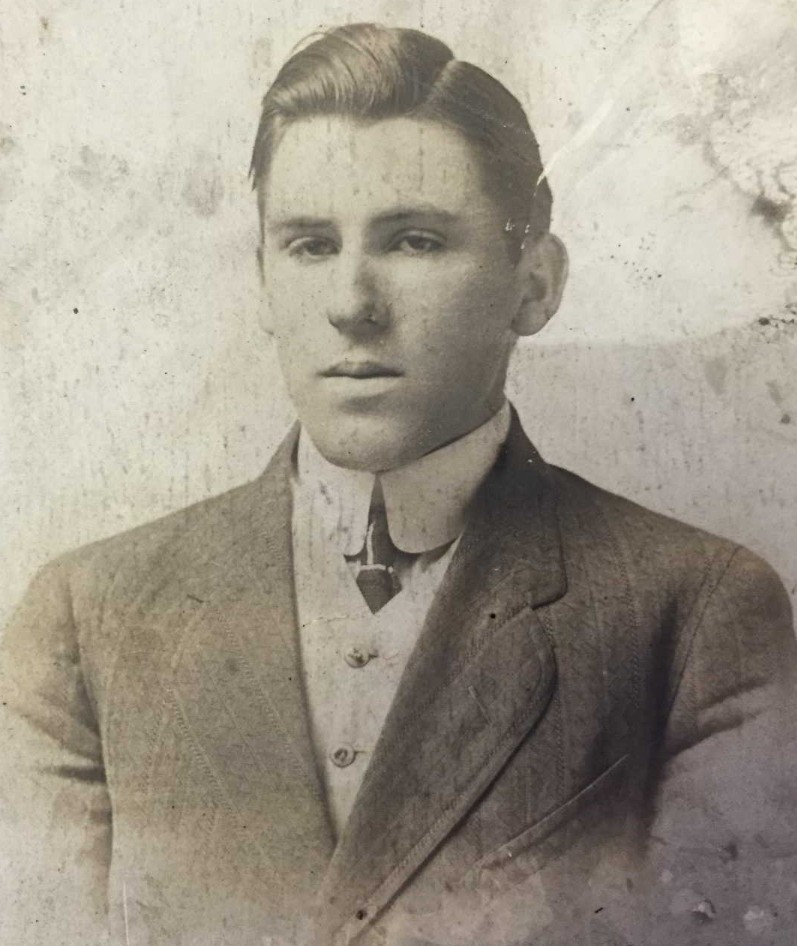

John Lindsay Morrison was born in Elma, Ontario, Canada, on 1st February 1894. One of eight children, his parents were farmers William and Elizabeth Morrison.

When John completed his schooling, he found employment as a bank clerk. He gave this up, however, when war broke out, enlisting in the Canadian Expeditionary Force on 24th August 1915. His service papers show that he was 5ft 7ins (1.7m) tall, with black hair, grey eyes and a dark complexion. No distinguishing marks were noted, but his religion was given as Presbyterian.

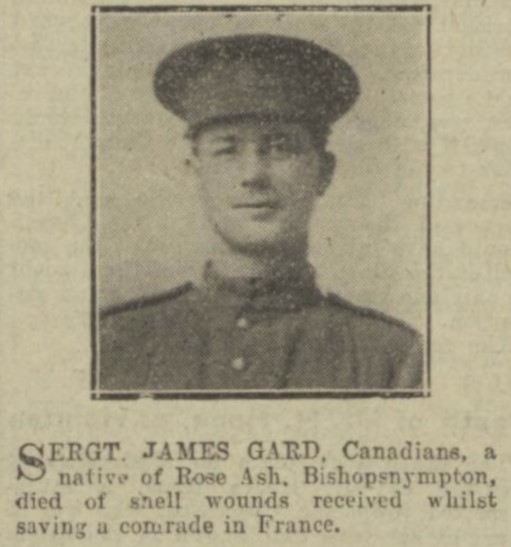

Private Morrison arrived in Britain on 11th April 1916. Assigned to the 32nd Battalion of the Canadian Infantry, he was billeted in Shorncliffe, Kent. His services records note that he arrived in France in June, and was promoted to Lance Corporal in February 1917. By May he was back in Britain, at Hursley Park, undertaking an aeronautics course with the Royal Flying Corps.

This seems to have been the route John wanted to take, and on 18th February 1918, he took a commission as a Second Lieutenant. He was based at the 29th Training Depot Station in East Boldre, Hampshire.

The role of a pilot was fraught with risk and, on 1st May 1918 – a month after the formation of the Royal Air Force – John was injured. His aircraft, an Avro 504, sideslipped while taking off from East Boldre airfield.

The court having viewed the wreckage at the scene of the accident, and having examined the wreckage area are of the opinion that 2nd/Lt. Morrison stalled Avro on a left hand turn and had not sufficient height to extricate the machine from the resulting spin.

Second Lieutenant Morrison would recover from his injuries, but more was to follow. Just three months later, on 31st July 1918, he had taken a Sopwith Camel up, and the aircraft crashed:

The cause of the accident was due to an error of judgement of pilot, in that he probably switched off at top of turn and had not time to get his nose down. Engine cut out at top of turn, causing machine to stall and then spin.

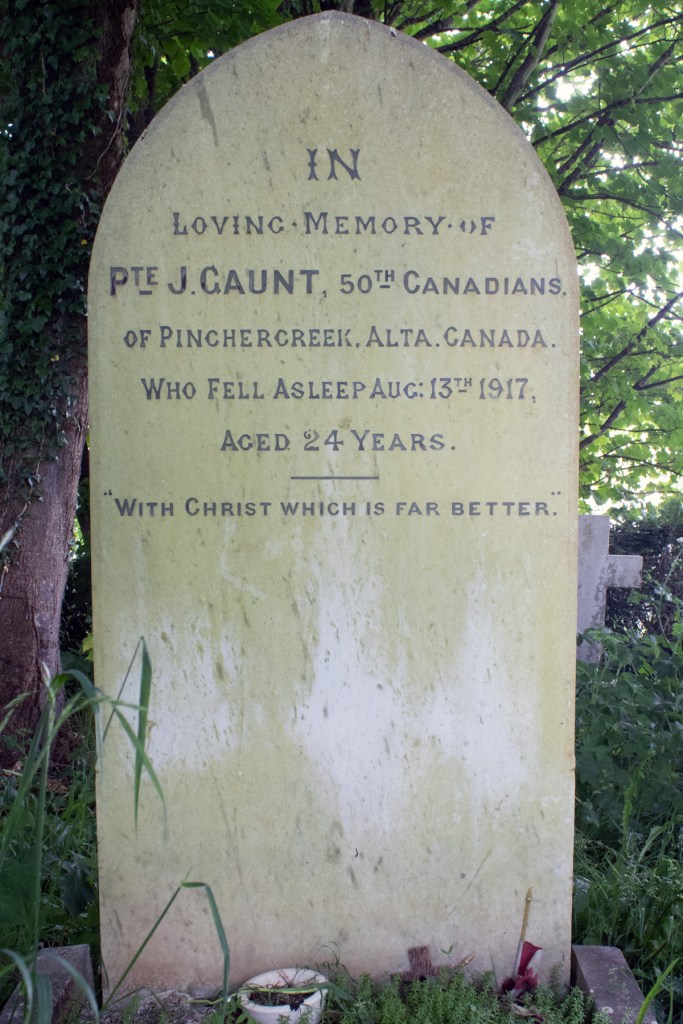

John was not to be so fortunate this time around. He was killed when the aircraft his the ground. He was 24 years of age.

Thousands of miles from home, the body of John Lindsay Morrison was laid to rest alongside colleagues from the squadron in St Paul’s Churchyard, East Boldre.