George Crossley was born on 30th December 1861 in the Stonehouse area of Plymouth, Devon. The oldest of five children, his parents were John and Charlotte. John died when George was only ten years old, leaving his widow to raise the family alone.

Left as the technical head of the family, George sought a reliable career and, in August 1877, aged just 15 years old he joined the merchant navy. After two years at the rank of Boy, he formally joined the crew, working as a Ship’s Steward’s Assistant.

Over the initial ten years of his service, George served on four ships, primarily the Royal Adelaide. In 1889, having seen the world, he signed up for a further decade. This new period of service saw him move up to Ship’s Steward, before working back in the assistant role.

In December 1899, George’s twenty years’ service came to an end. Charlotte, by this time, was in her mid-60s, and perhaps he felt it better to spend time ashore with her, rather than leaving her alone.

His experience did not count for nothing, however, and he found employment as a labourer in the Naval Dockyard in Chatham, Kent. And so another fourteen years passed, before war rose its ugly head.

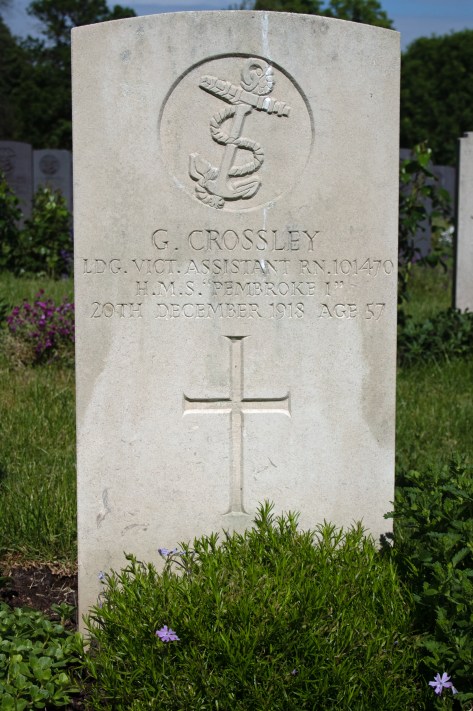

George was called back into service at the start of the conflict, and resumed his role as a Ship’s Steward’s Assistant. Over the next few years, he served on a couple of ships, but the majority of his time was spent at the shore establishments in Portsmouth, Dover and Chatham. In 1917, George gained the rank of Leading Victualling Assistant, giving him some of the responsibility for the food stores at Chatham Dockyard.

Towards the end of 1918, George seems to have been in the east of the county, when he fractured and dislocated his left ankle. Little specific information is available, but it seems that he was admitted to the Royal Infirmary in Deal, but died of his wounds on 20th December. He was ten days short of his 57th birthday. An inquest later that month reached a verdict of accidental death.

Brought back to Gillingham, George Crossley was laid to rest in the Woodlands Cemetery in the town.