Victor Rous Duckett was born in Margate, Kent, on 2nd September 1887, the youngest of seven children to publican and stonemason Charles Duckett and his wife, Emily. Tragically, both of Victor’s parents died when he was young: Charles passed away on 31st October 1891, while managing the Clifton Arms public house; Emily passed away just four months later.

Victor’s brothers Charles and William took over the running of the pub, and, understandably, took on the responsibility for the family. The 1901 census records that he was one of eight boys boarding at a ‘private school’ in a house in Stanley Road, within walking distance of the Clifton Arms. The school was managed by James and Mary Hawkins and had one master, Alexander Smith.

When he left school, Victor found work as a compositor, setting type for a local printer. In the meantime, while his brothers were still running the pub, his three sisters had set up a ladies’ outfitters in Broadstairs, where they employed an assistant, Amy Leggett. Victor and Amy became close and the couple married in Sussex – where Amy was from – in the spring of 1911. They set up home in Croydon, and went on to have twin daughters, Caroline and Dorothy, the following year.

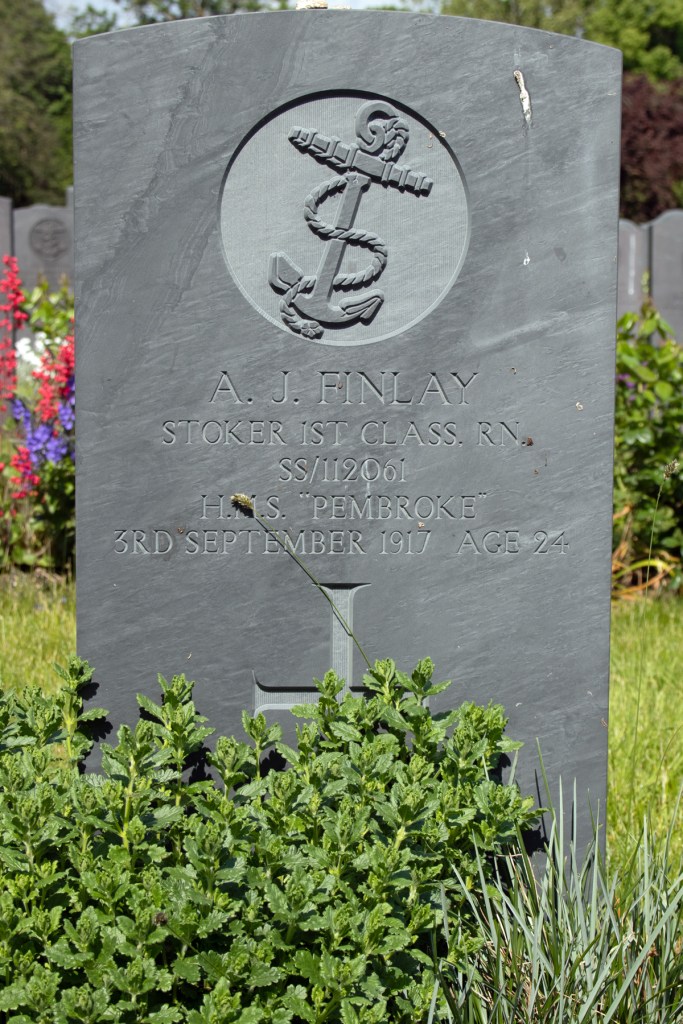

War was on the horizon, and Victor was called up on 27th February 1917. He enlisted in the Royal Navy as an Ordinary Seaman, and was sent to HMS Pembroke, the shore-based establishment in Chatham, Kent. His service records show that he stood at 5ft 10.5ins (1.79m) tall, had brown hair, blue eyes, and a fresh complexion.

HMS Pembroke was extraordinarily busy when Ordinary Seaman Duckett arrived there. Temporary accommodation at Chatham Drill Hall had been set up, and Victor found himself billeted there for the summer.

On the 3rd September 1917, the German Air Force carried out one of its first night-time air raids on England: Chatham was heavily bombed and the Drill Hall received a direct hit. Ordinary Seaman Duckett was badly injured and died of his wounds in hospital the following day. He had celebrated his thirtieth birthday just two days before.

Victor Rous Duckett was laid to rest, along with the other victims of the Chatham Air Raid, in the Woodlands Cemetery, Gillingham.

Victor Duckett

(from ancestry.co.uk)